by Allie Nicodemo – contributor

News@Northeastern

When Hongli (Julie) Zhu first came to the United States in 2007, she was surprised by the prevalence of single-use plastic containers at supermarkets and restaurants. “The material is cheap and convenient, but most of these containers are not biodegradable,” says Zhu, an assistant professor of mechanical and industrial engineering at Northeastern. According to the Environmental Protection Agency, 27 million tons of plastic were diverted to landfills in 2018. Plastic doesn’t decompose over time. It gets broken into smaller pieces known as microplastics that pollute rivers and oceans.

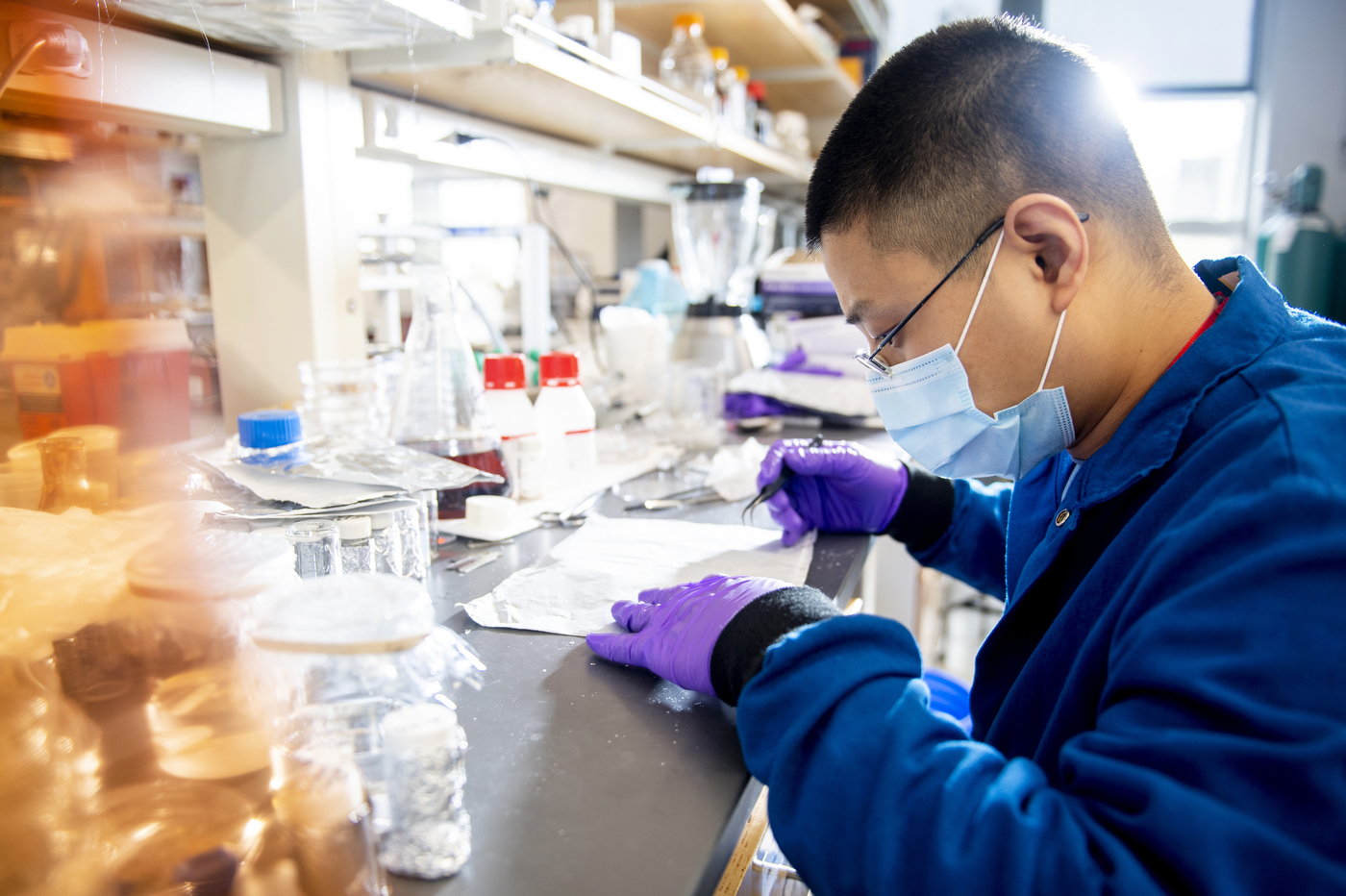

Hongli (Julie) Zhu, an assistant professor of mechanical and industrial engineering at Northeastern, developed a way to create biodegradable food containers using sugarcane and bamboo fibers. Photo by Ruby Wallau/Northeastern University

Hongli (Julie) Zhu, an assistant professor of mechanical and industrial engineering at Northeastern, developed a way to create biodegradable food containers using sugarcane and bamboo fibers. Photo by Ruby Wallau/Northeastern University

Zhu knew she wanted to develop a better alternative to one-time use plastics. In a paper published recently in the journal Matter, Zhu and her research team describe their solution: Turning a sugarcane byproduct into a sustainable, compostable, and inexpensive material that’s durable enough to serve as tableware, and that biodegrades within 60 days.

With a background in wood chemistry, Zhu initially thought about using wood pulp to create her new material. But working with wood requires planting trees, which would make the manufacturing process too environmentally intensive. She sought a more sustainable solution and found inspiration in an unlikely place. “I have a 4-year-old son, and he eats a lot of candy,” Zhu says. While examining the ingredients in his treats, Zhu had a realization: Sugar is a natural, mass-produced material with no synthetic chemicals. What if she collected the pulp byproduct of sugarcane production and used it to create a sustainable alternative to plastic?

Sugarcane pulp, known in the industry as bagasse, is one of the most prevalent food waste products in the world. It is safe to consume and naturally biodegradable. But bagasse fibers are relatively short and not particularly strong. That’s a problem, since any material used to make tableware needs to be durable and grease resistant.

|

|

Hongli (Julie) Zhu, an assistant professor of mechanical and industrial engineering at Northeastern, developed a way to create biodegradable food containers using sugarcane and bamboo fibers. Photos by Ruby Wallau/Northeastern University

To improve the mechanical strength of the bagasse material, Zhu and her research team mixed in bamboo fibers. The result is a completely natural and biodegradable material that is sufficiently durable to be molded into containers strong enough to hold food and liquids. And since bagasse and bamboo fibers are made up of similar underlying chemicals (cellulose, hemicellulose, and lignin), the material doesn’t require any additional processing to separate different components, unlike some currently available options. “That’s why I’m very passionate about this material,” Zhu says. To test how the material would degrade over time, Zhu and her students devised an experiment. They buried a container made of the new material in the lawn outside of Northeastern’s Mugar Life Sciences building and checked on the container every 10 days. They found that the material began breaking down after about 30 days and disintegrated almost completely after 60 days. This is a huge improvement over currently available compostable containers, some of which require specialized industrial equipment and high temperatures to actually decompose, Zhu says.

Ever since her research was published, Zhu has been fielding requests from sugarcane production companies interested in collaborating with her team. She says these companies are excited about the potential of putting their waste byproduct to good use. Zhu has filed for a patent and will work with industry partners to begin commercializing a product. Her hope is to create tableware that’s just as convenient and inexpensive as the plastic options, without the extreme environmental cost. “The end goal is to tackle the plastic pollution problem,” Zhu says.

Written by